The Data Handbook

How to use data to improve your customer journey and get better business outcomes in digital sales. Interviews, use cases, and deep-dives.

Get the book Sustainability is one of those hard-hitting topics which has taken its time to lodge into the public consciousness and bristles with seemingly insurmountable challenges as one finally braces to tackle it. To make no excuses in the process is to commit to a long, often arduous project of transformation for any brand. But in the third decade of the twenty-first century, there is also no other ethical choice to make.

Sustainability is one of those hard-hitting topics which has taken its time to lodge into the public consciousness and bristles with seemingly insurmountable challenges as one finally braces to tackle it. To make no excuses in the process is to commit to a long, often arduous project of transformation for any brand. But in the third decade of the twenty-first century, there is also no other ethical choice to make.

Ethics, of course, is one of the key themes underlying the concept. A sustainable brand is one that behaves ethically towards the environment, is mindful of culture and takes social responsibilities. It's hardly possible to declare perfect achievement in one of these aspects let alone all of them. So where does a brand start — what does it mean to be sustainable?

Dimensions of sustainability

Broadly speaking there are the three aforementioned aspects: environment, society and culture. Environment is the footprint of the brand, the all-encompassing effects of its operations: raw materials, transport, packaging, industrial waste, power source of the machines and how everything is put together. Treatment of animals could also be considered within this purview and so follows all labels from CITES and MSC to FSC and Rainforest Alliance Certified.

Societal aspects are centred around the human angle. Are fair wages paid to the workers, do they have job security and necessary benefits? And how active the brand is in championing its beliefs and the customers that identify with them. This is what drives brands such as Ben & Jerry's to pull out of certain cities and others such as Warby Parker and Toms to donate free products to the needy for every single unit sold. There is no clear line here between responsibility and activism which could also at times be a lightning rod for criticism such as #justburnit in 2018 where some figures from the progressive end of the political spectrum also called out Nike for 'woke washing'. At a fundamental level, brands earn Fair Trade and SA8000 certifications for their efforts in this regard and also some hybrid ones such as GOTS which take both social and environmental aspects into consideration.

The most vaguely defined aspect is the third one, cultural. It tends to surface in raging debates online about 'cultural appropriation' and could be viewed within the framework of cultural hegemonies and power relations. Does a brand credit and involve communities whose works it draws inspiration from? If craft heritage is digitised and reproduced, does it benefit the indigenous craftspeople? There are no easy answers here. But when discussions keep appearing on cultural responsibility vis-à-vis Chanel runway shows and H&M's recent Wanderlust collection with Sabyasachi, it seems that we are still grappling with some late-stage implications of globalisation.

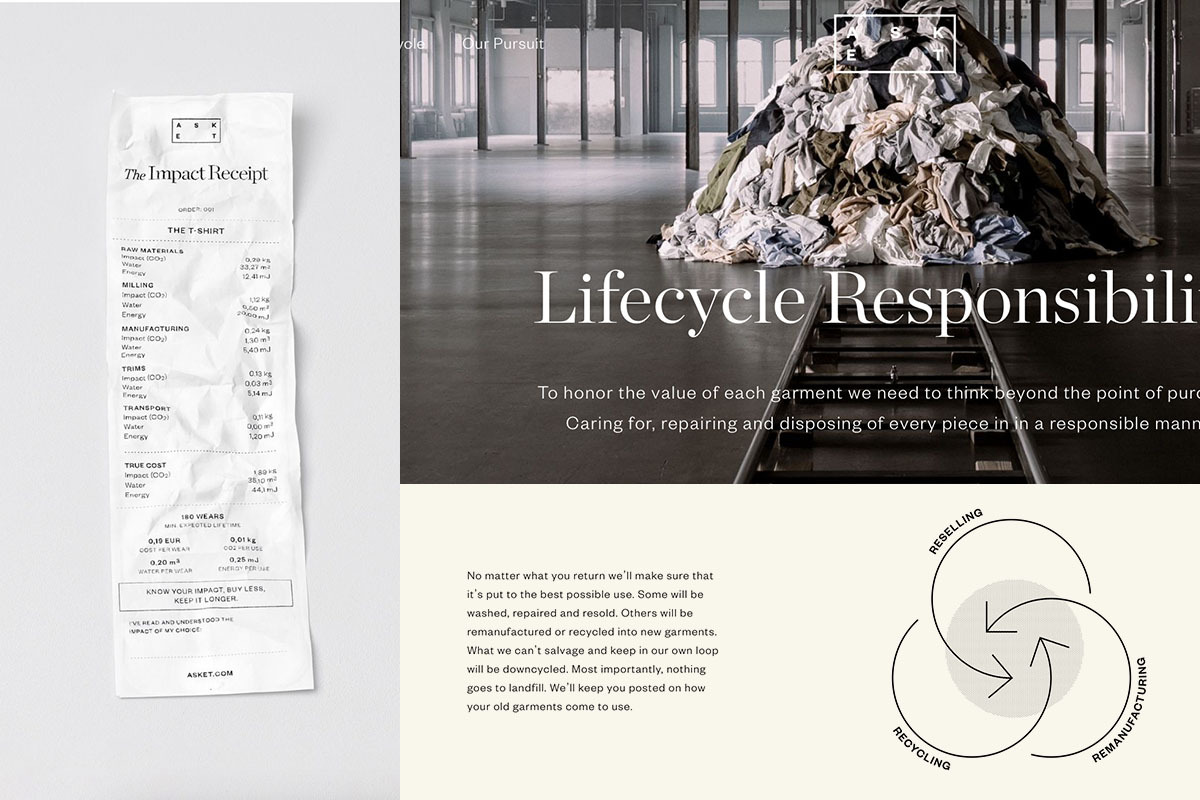

Asket has a variety of initiatives covering transparency and lifecycle management.

How far can you go?

The first step for anyone to take towards becoming a perfectly sustainable brand is to acknowledge that it's a journey and a long one at that. Also, depending on the type of brand that you are — retailer, producer, marketer or vertically integrated operation — the options immediately available to you vary at length.

However, there are elementary things anyone is capable of doing, such as committing to using minimal packaging or using organic raw materials, even if full-scale traceability and lifecycle management à la Asket is unfeasible. The plan has to be made for a timeline of many years with the business priorities aligned to ensure momentum. Even Asket doesn't market its products as 'sustainable' and opts for 'transparency' and 'responsibility' instead. Few businesses beyond local micro-brands can truly lay claim to the former. And a carbon-negative badge is not necessarily a good thing.

Mirages

Anyone who looks for 'green' products online has surely come across 'greenwashing'. The term has been thrown around for good reason, just like 'rainbow washing', 'queer baiting' and a fairly long list of related terms. Between all the fastidious proprietors of responsibly sourced and produced products, there are also many who choose to go the easy way of purchasing carbon offsets and using the occasional recycled cotton t-shirt to market themselves as eco-friendly.

It's not always done in bad faith but it's always a half-measure. Organic cotton is taken at face value to be better than its GMO counterpart but it also produces less fibre and takes up more land, and there are conflicting reports about its thirst for water. The vast water-scarce areas of South Asia where the bulk of cotton is grown also begs the question of whether cotton is really the future of sustainable clothing. Silk is one of the most resource-efficient natural fibres but it involves questionable treatment of animal life. Recycled paper has a lower footprint than FSC paper only if it's mostly composed of recycled fibres and has been heated and de-inked using newer technologies and preferably not powered by coal.

There's also the carbon-offsetted delivery and the recent trend of planting a tree for every product purchased. They are without a doubt efforts to be lauded for their contributions towards preserving or even improving our environment but the impact is unclear. Who maintains these newly planted trees and for how long? Which species are planted and are they native to the biome? While new trees sequester carbon faster than the grand old-growth, they make the necessary impact only over years of adding biomass. Even at a lower pace, by sheer amount, older trees have an outsize impact and we need both.

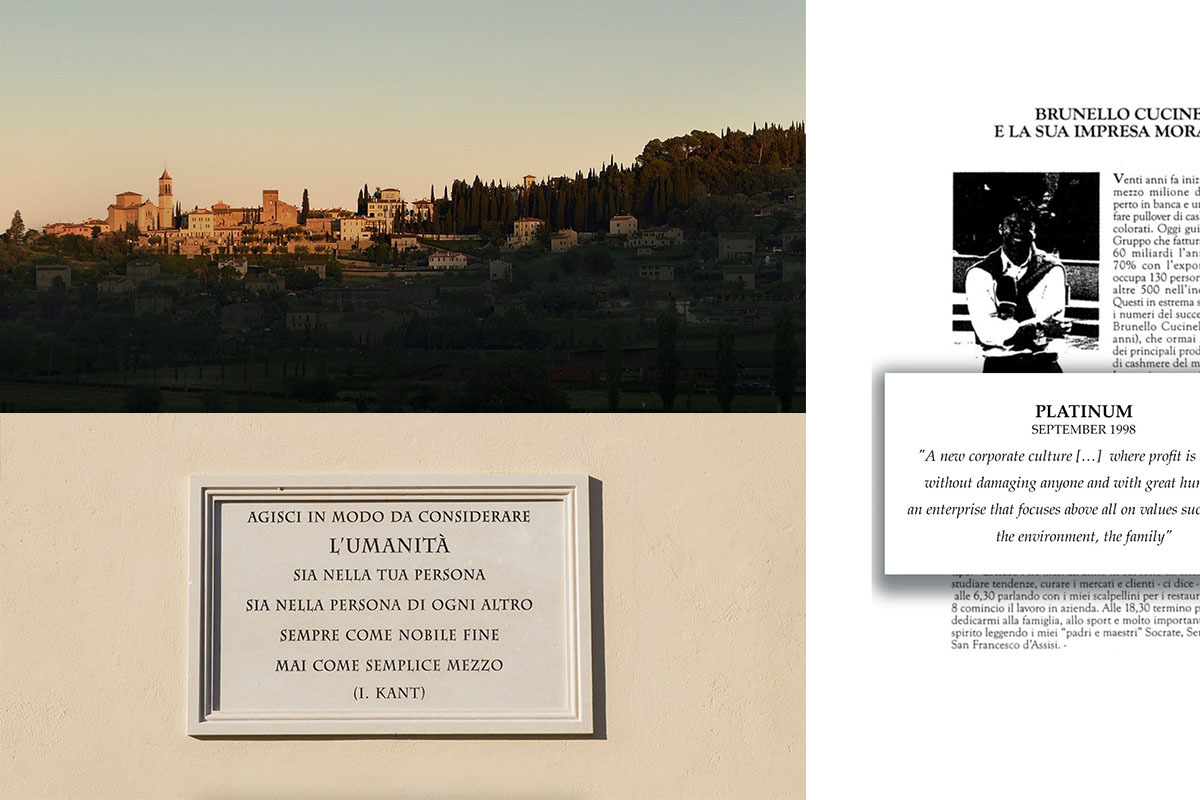

Brunello Cucinelli shows an alternate path for luxury brands, reviving a whole village in the process they label ‘humanistic capitalism’ which has workers and the community of Solomeo at its heart.

At the end of the supply chain, a t-shirt becomes sustainable only when multiple criteria are met, from the source of water to the dyes used in the packaging and whether it was made by someone who had a shot at enjoying life. A lifestyle brand becomes sustainable when it incorporates locally grown linen and hemp while also investing in reclaimed wool, like Patagonia, which has gone well beyond its days of introducing polyester fleece to become one of the forerunners in reuse and long-use. It's not an easy task and there are many delicate lines to traverse such as choosing between being vegan and environmentally friendly, which are not always the same thing.

But it has never been easier to start. A wide range of brands are already doing innovative things on various fronts to push us closer to the ideal. And many of them are focused on helping others to reach their own sustainability goals. There are also things to be re-learned from earlier times.

Ideas to consider

Reusable packaging

Recent attempts at reducing the packaging footprint, in particular for ecommerce, has focused on cutting down on the amount of packaging and making them reusable. Recyclable cartons and paper wraps have already been in use for decades but RePack broke new ground by introducing reusable packaging as a worldwide service. The approach is not entirely new — hyperlocal sectors like food delivery in Seoul have been doing it for decades — but for the majority of businesses it was unattainable. And for those who hesitate to use it for branding or other reasons, there's always the option to revise and reduce regularly, like Asket's undertaking from earlier this year, or follow in Pangaia's footsteps and introduce compostable packaging.

Fewer returns

Closely associated with the deluge of brown boxes is the trouble in returning them. There is not always an allowance for repacking the over-taped boxes and they don't necessarily stand up to the pressures of the delivery. The problem extends also to plastic packs and not all retailers provide ready-to-use return labels either. But should returns even be encouraged? It's a problem that even the most environmentally responsible brands struggle to tackle. There are ways this could be addressed at the product level. Provide as accurate representations of the product as possible and detailed specifications. For clothing, mention the models' height and weight, give measurements and advice on getting it right. With ever-improving AR technologies, there is even the possibility to do accurate virtual try-ons for some items. Even after all this, to avoid 'supercharged window-shopping' there could be rewards doled out to the customer for not returning items.

Assisted resale

Just over a week ago, Marimekko launched a limited 'pre-loved' selection online, following a long chain of brands that have partnered with marketplaces or self-released pre-owned collections online. Some even have longstanding relationships with authorised pre-owned resellers like what luxury watch brands have championed for years. Marrkt is another example, where a denim retailer decided to make a foray into pre-owned fashion consignment, and continuously host sales from menswear influencers and brand promoters. This is a sector projected to grow significantly over the coming years and something no brand — retailer or producer — can afford to overlook. And customers demand it too, with a need for authenticity and assurance of quality, things which brands are in a unique position to ensure. The gradual increase in perception of value of 'old' items can also have a positive effect on sustainability pursuits as previously disposable items are suddenly more valuable and consequently could also be priced higher. For platforms like Vestiaire Collective, Grailed and HEWI, the need for collaboration is equally attractive, to get exclusive items and weed out counterfeits.

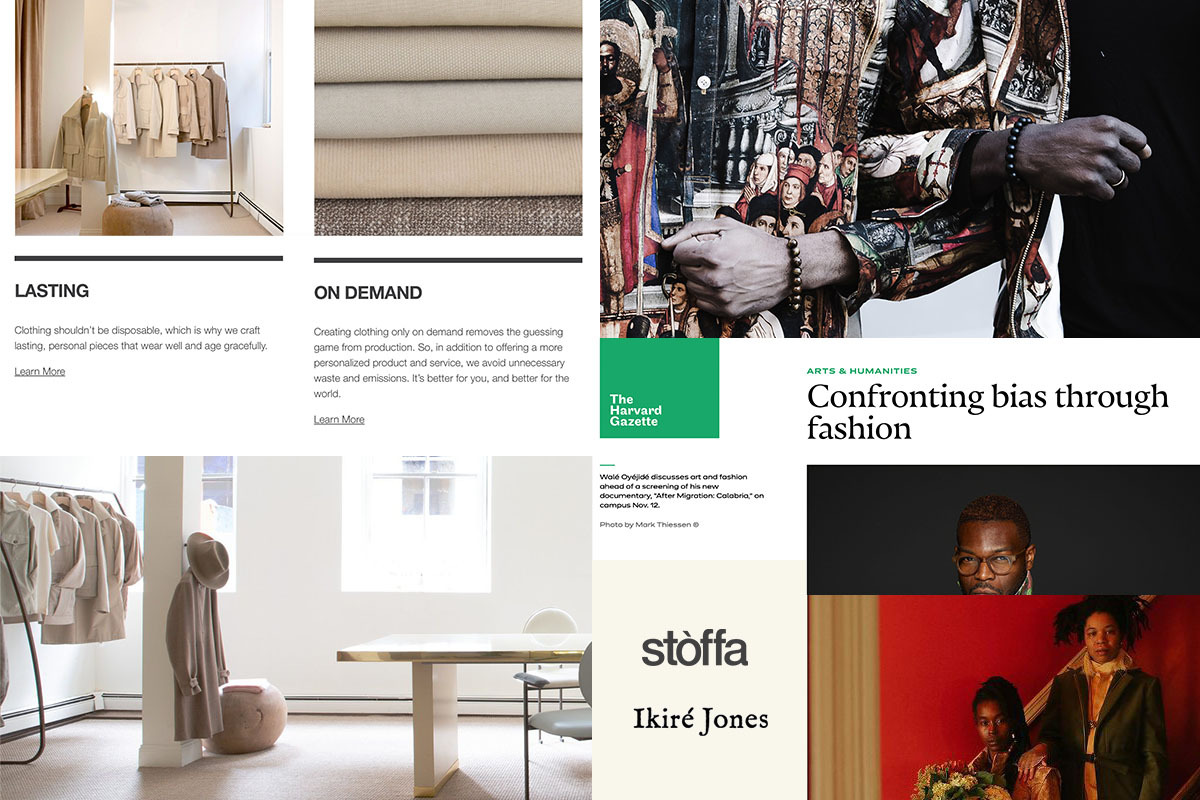

Stoffa and Ikiré Jones have very different brands but they both focus on high-quality products and small runs, often made to order or measure.

Sell less but better

Sometimes the best way to go forward is by looking backwards and one such tradition which was alive well into the mid 20th century and declined during its latter half is the ritual of getting things made to order. High-end furniture and lighting brands have kept on doing so but in most areas of clothing and personal effects it's become limited. But now many brands, even outside the domain of made-to-measure tailoring are bringing it back, often with the best of customer service. The customer is advised at each step as to what exactly she wants, all necessary adjustments pertaining to sizing and other requirements are taken care of, and what they have in hand at the end of the process is something made to their needs, and often unique at that. There's also a difference in personal attachment between something off-the-rack and something that was made for you — something brands would be well advised to explore. It's unfortunately also a matter of slow behaviour change on part of the customer which just takes time.

Another angle to selling less that was pursued earlier was renting out clothes but there have been concerns about the footprint of sending all these items back and forth and some studies have concluded that they're worse. But there could still be ways omnichannel brands could improve on this by utilising their physical presence and also when it comes to luxury goods, there is the potential to lease out a hot item during the first few seasons and later putting it for sale on a marketplace.

Taking the leap

So to sum it all up, for any new brand that wishes to make an appearance in the market with an unwavering commitment to sustainability, or for earlier ones to make a new pledge, there are a multitude of inspiring stories and many places to start. Look to Asket or Arket if you want to start with transparency and perhaps even get to a blockchain implementation that goes all the way to the person who made the item; look to Carl Hansen & Son, Stoffa or Ikiré Jones for savvy social presence and making made-to-order attractive for contemporary times; look to Bokja and Patagonia for an activist-minded approach that respectively prioritises artisanship and environment.

The important thing is to decide what sustainability means to you and which dimensions you are willing to address, at least at first. Then it's a matter of continuously pursuing those goals while setting new ones. And it's necessary to ensure that once a goal has been achieved it stays that way. Suppliers and partners are notorious for falling back on promises without regular inspections and having shared incentives that work for everyone. This is a collaborative effort that has to go all the way from the workers harvesting raw materials to the customer opening her long-awaited package.

Download our Digital Sales 2025 trend report to get an overarching view of the key trends shaping digital consumer sales across the five customer journey stages. The report includes interesting examples from some of the most interesting brands in the industry: Amazon, Nike, Adidas, Walmart, Pinterest, and many others. Download the report and learn from forerunners how to make the most of digital retail!

The Data Handbook

How to use data to improve your customer journey and get better business outcomes in digital sales. Interviews, use cases, and deep-dives.

Get the book