The Data Handbook

How to use data to improve your customer journey and get better business outcomes in digital sales. Interviews, use cases, and deep-dives.

Get the book

I.

"A purchase on the horizon, a panoply of temptation. Can a curious soul desist?"

The tall, imperious shop associate played by Fatma Mohamed delivers one of her cryptic-alluring lines as her customer (Marianne-Jean Baptiste) regards the red dress with hushed-breath fascination. The setting is a quaintly unsettling department store sometime in the 70s in England, one of those places where mannequins reveal sinister glances and the air is unmistakable with its sense of place.

In Fabric, director Peter Strickland's darkly satirical ode to the charms and morbidity of consumerism is filled with such surreal moments but it was the department store ritual that caught my attention. The almost hypnotic effect conjured forth by a combination of atmosphere and etiquette; how the mere act of vague-minded browsing about for a dress can be constructed as an elevated experience in the retail environment. Does that exist anymore?

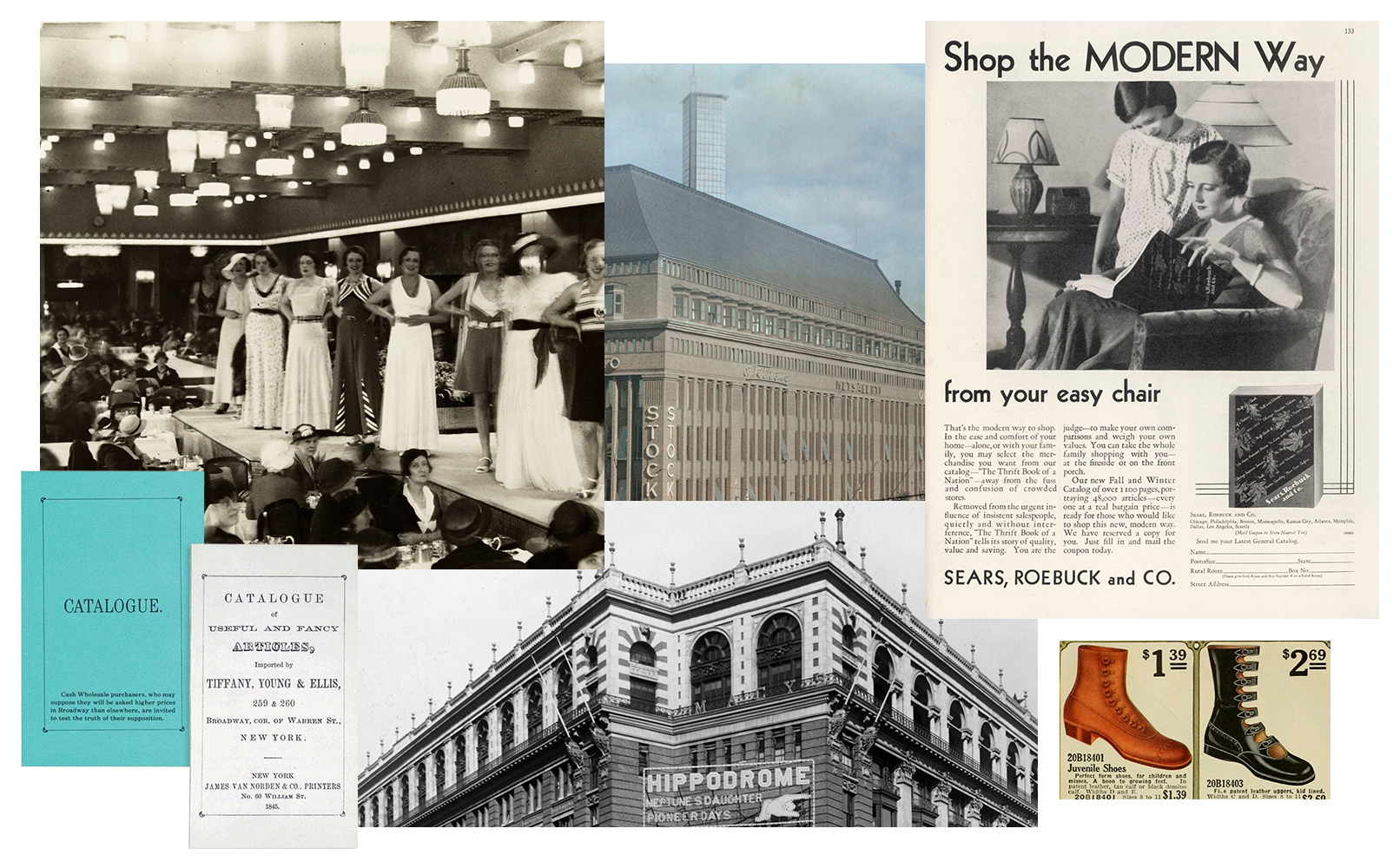

Luxurious origins

The first department store in the world, Le Bon Marché in Paris, when it opened its doors in 1852, was an enchanting showcase far removed from the ominous Dentley & Soper’s in the film, where affluent patrons could idle through well-stocked departments in an ambience steeped in luxury. Goods displayed on mannequins and revolving stands took on the role of aspirational objects of devotion offering transformational possibilities in a rapidly urbanising world. The salient features of retail would become established: fixed prices and seasonal sales, assured refunds and exchanges, glamourous advertising and shop displays.

On the far side of the Atlantic, other enterprising merchants would soon introduce simpler pleasures to a wider clientele, furnishing rural households with all manner of provisions through mail-order services.

On the cover: Detail from 'Le Magasin de nouveautés (Le Bon Marché)' by Alexandre Lunois.

Clockwise from top left: A fashion presentation in progress at Le Bon Marché, 1925; Stockmann Helsinki, circa 1930; Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalogue advert from early 20th century: button boots and other styles on sale in the catalogue; Macy's Herald Square flagship in New York; mid-19th century Tiffany's Blue book.

Catalogue for the masses

The Sears-Roebuck and Montgomery Ward catalogues, when they manifested their signature forms in the late 19th century were hardly the first of their kind but what made them distinct was the focus on the customer. With expansive, vivid volumes replete with illustrations, they urged the material longings of readers who were heretofore limited to local general stores, and provided them at unmatched prices. There was also the money-back guarantee. Testimonials accordingly flowed from delighted customers to adorn subsequent issues.

An often overlooked impact of the mail-order catalogue, in particular the Sears-Roebuck, is the democratising effect. In the turn-of-the-century United States, when the national postal network was expanded to serve the vast hinderlands of the South, racial segregation was rife in the small towns, and procuring daily necessities routinely led to condescending treatment at the hands of the store owners. Now, with the catalogues, even barely-literate workers could order anything they needed by scribbling on pieces of paper—and the orders remained anonymous. No one living outside of cities had to make do with sustenance, if they could afford it.

Big expansion

Decades afterwards, retail too would follow the path of post-war prosperity which led away from downtown avenues to the suburbs. As cities expanded to accommodate flocks of wide-eyed young aspirants arriving from the heartlands, these suburbs became the new focus of commercial expansion and businesses rushed to cater to them with sprawling new outposts — the shopping malls and big-box stores.

In this age of efficiency and gleaming highways, the pull of the high streets weakened while the malls dazzled with their seamless blend of entertainment and commerce. Whereas once a family needed to trip-traipse their way across parks, stores and restaurants, all the while attending to the continuous demands of their toddlers, now they were offered everything in one destination, with all the parking they could want. The fountains and roller coasters arrived, ever more ambitious architecture, and the blueprint was rolled out across the high-income world by the 80s.

If the department stores were about affluence and the mail-order catalogues about access, the malls were about shopping as activity. Enveloped in a buzzy cocoon of excitement, the new shopping centres anchored all other leisure-time pursuits — cinema, games, dining — around the central consumerist ritual of shopping. The realities of pastoral and socialist societies would however continue on in their different veins as they lacked the requisite proliferation of mass production and access to capital.

But before the new model could fully disperse and flourish, technology with its intemperate rhythms introduced a further development that took efficiency to another degree and the face of shopping would change again. Introducing: the World Wide Web.

II.

The end of the last millennium was in many ways a tumultuous period, when lifestyles and businesses changed more transformatively than in the many centuries preceding it. For most of history, business to consumer trade was a small and personal affair with varying levels of refinement. Trade empires such as the East India Company formed but the spices and silk were still sold at small, discrete outlets. And these will remain in business, some to be inevitably eclipsed by the venerable department stores and run over by malls, others establishing themselves as heritage outposts, and even more arriving on the scene with new ideas; retail continues to re-invent itself.

But deep under these tides of change, the connection between the good and the consumer was also fundamentally transformed. From the scarcities of wartime eras and the mode of doing business where one chose and ordered a good with much care and kept using and reusing it until the last threads gave out, now there was a surplus of everything. With their newfound affluence, consumers bought more readily available items and valued them less. Only a select few were worthwhile to service. The rest were transitory commodities with no personal connection, constantly replaced by the market with something faster, shinier, better.

Still, the appetite for personalised items never entirely disappeared. The tailors, saddlemakers and haute-chocolatiers would continue serving their select clientele and discover the promise of emerging markets, but their trade as a share of the economy was in steady decline. The world was getting used to immediate and endless gratification.

Clockwise from top left: 1 - 5, scenes from mid to late 20th century Americana; life continues as usual in some parts of the world.

Clockwise from top left: 1 - 5, scenes from mid to late 20th century Americana; life continues as usual in some parts of the world.

Online spheres

To this heady excitement of the 90s, the first dot-com businesses arrived, as exuberant upstarts taking the remote-shopping innovations of the day to the newly public World Wide Web. It's sometimes wrongly assumed that online commerce was pioneered by business to consumer enterprises. From the late 60s, there was increasing interest among businesses to interconnect their computing systems for easier exchange of information, and transactions. The format was refined and coined EDI — Electronic Data Interchange — and along with teleshopping constituted the proto-online infrastructure on which ecommerce would be built upon. But teleshopping was essentially the mail order catalogue broadcast on television, EDI was the true novel technology.

The era is still chiefly remembered for the birth of Amazon, eBay, the bust of Boo.com and frenzied speculation that led to a resounding market crash by the end of the decade. The businesses that survived grew from being modest online vendors of books and few commodities to global marketplaces selling nearly anything; as graphically described in Amazon's logo, all from A to Z.

Everything for everyone

Ecommerce with its singular capacity for broad reach and deep inventory is a retail model unlike no other. Like Amazon is much more than any physical store — perhaps more like a mall, but again a city seems like more of an apt description. It produces some goods of its own, which it sells; it also sells goods marketed and made by others, hosts other stores as a marketplace, provides streaming services and even operates as a library of sorts. The Amazon I see is almost never the Amazon another does, exhibiting uncanny versatility and understanding to its customer like few brick-and-mortar establishments could aspire to. If a city, it is also one accessible from anywhere.

Notwithstanding that Amazon and eBay are not the rule but exceptions, the ascension of retail to the Web brings new modalities to the landscape of shopping that mere historical precedents could not draw comparison to. In a very short span of time, there were now millions of places to shop from; stores, auction sites and marketplaces around the world. Soon also platforms like Instagram, where shopping is not the norm but a latent possibility. Goodbye to opening hours and planned visits. If malls blended shopping with recreation, ecommerce brought it straight home.

Trails and echoes

So with the stores disappearing into the digital fabric surrounding our lives, any contemplation of shopping now begins with the phone — to be precise, the smartphone, in many ways less phone and more personal computer. When we talk of user experience in ecommerce, it's more about how it is to place an order with the phone than the unpacking experience. If the purchase is made at a physical outlet, the decision yet often follows from an earlier browsing session.

At face value, the convenience of this is indescribable. Everything at our fingertips exactly as it was promised. The Futurist Manifesto of a hundred years ago could not have hoped for better. And the stores keep constantly adapting to our preferences, so much more patient than shopkeepers and infinitely more fastidious. On the other side too — for artisans and small-time traders hoping to find better markets for their wares. When it works to our betterment, 21st century ecommerce is nothing short of a miracle.

The unfortunate problem is that it always doesn't. The contemporary shopping experience is also one of persistent ads à la Terry Gilliam, echoing through cyberspace when we are busy skimming through news and always reminding us that things are just around the screen. The demands of a digital lifestyle come here into sharp collision with our ancient brains wired for a history of scarcity. And activities which would go undisturbed in the past would continually need to vie for attention. Advertising is indeed nothing new, but the way in which its online embodiment seamlessly packages our past motive, present action and potential fulfilment makes it radically different from the antecedents.

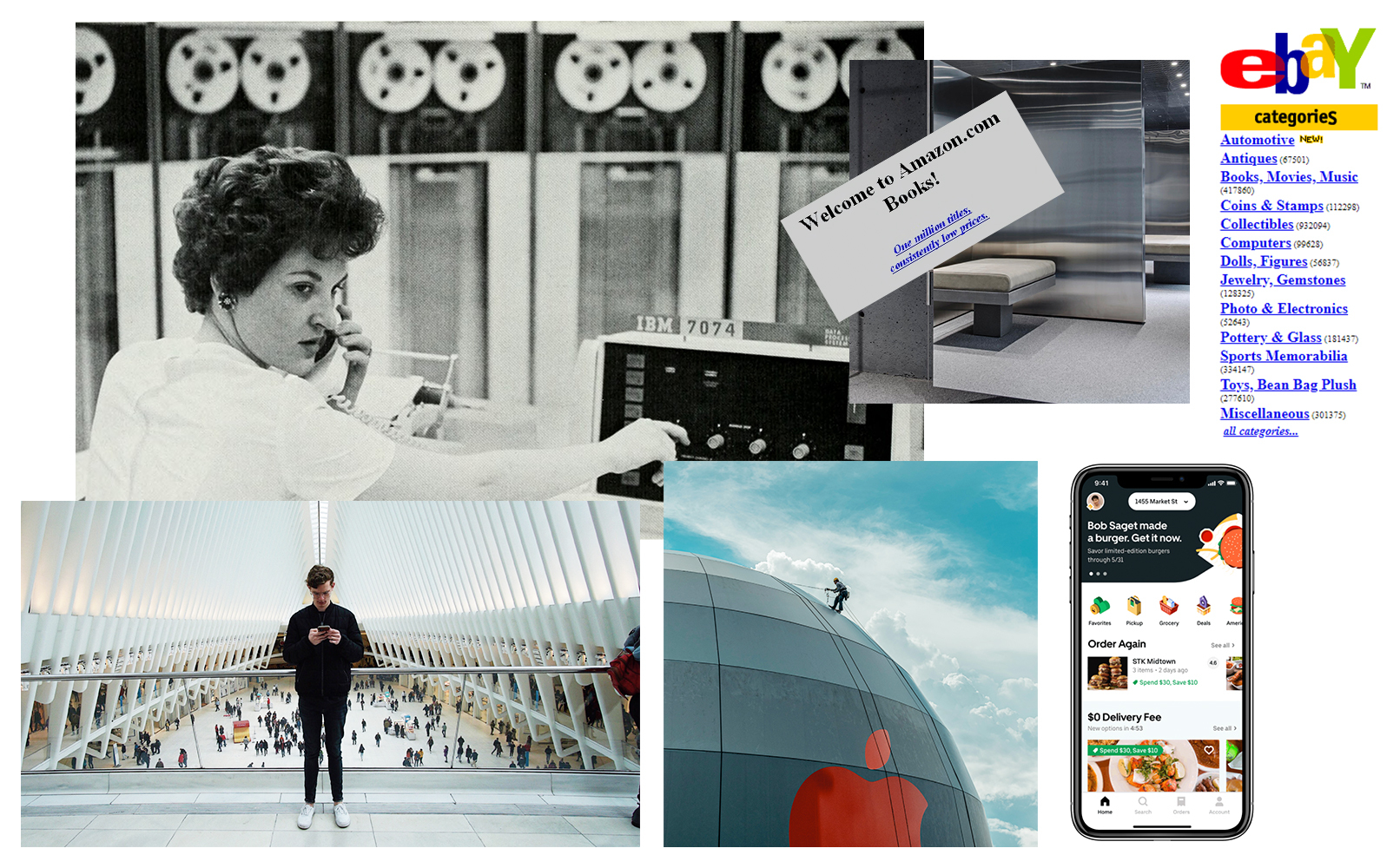

Clockwise from top left: Operator on an IBM 7074, early 60s; screenshot of Amazon.com, 1995; fitting rooms at the SSENSE flagship store, Montreal, 2018; screenshot of eBay, 1997; UberEats, 2019; Apple store in construction, late 2010s; shopping at the One World Trade Center, New York, late 2010s.

Clockwise from top left: Operator on an IBM 7074, early 60s; screenshot of Amazon.com, 1995; fitting rooms at the SSENSE flagship store, Montreal, 2018; screenshot of eBay, 1997; UberEats, 2019; Apple store in construction, late 2010s; shopping at the One World Trade Center, New York, late 2010s.

III.

Amidst the surprises and tribulations of the past many months, it's hard not to look at the state of physical retail and wonder — is this how it ends? It seems like a long time coming, the strength having drained out of the machinery long ago and barely kept running so as not to break the cycle. And the cycle itself, propelled by ballooning credit and aggressive competition from an ever-increasing roster of incumbents, looks increasingly questionable against the backdrop of resource depletion and lasting environmental change.

Online retail fares no better when it comes to many of the real-world issues we face but it's the most adaptable as this crisis has proved. The platforms and web infrastructure extended a lifeline to many vulnerable businesses, keeping them afloat, and relying on the efficiency advancements the logistic chains had built over decades, also managed to provide many in need with essential supplies. The physical presence of some of these businesses almost appears superfluous now. Do we need all these stores?

The shape of cities

There are few things inevitable about the cities and towns we live in. Each has its unique developmental history within larger tapestries of regional and national histories. The older ones in Europe and the Americas tend to have central squares and churches with avenues and parks spreading out. Brand new metropolises take a different approach, prioritising roadways over cobbled streets, yet keeping many of the familiar elements. Among these, a significant portion of real estate dedicated to shopping.

Does this resemble an ideal state of affairs? Dense neighbourhoods lie at the heart of many cities where parks are nowhere to be seen and shared public spaces seem like a luxury. An ideal world might allocate more real estate to these and allow people more breathing space. After all, rows of garments and appliances awaiting a prospective buyer bring little to the spirit of a community.

Consolidated paradigms

Wishful though it may seem, there are contemporary concepts which reframe these questions with fresh perspective, resulting in integrated omnichannel experiences like the SSENSE flagship in Montreal. The role of a physical store in the digital age is primarily about experience. The sensory, tactile information that reaches our minds as we run our hands over a soft flannel, the feeling of a chaise longue, the scent of cologne, and feeling a brand space. Until such a day when technology arrives to represent tangible matter with perfect fidelity, this is the unique domain of physical retail. Not the price, provenance or technical composition.

Stores can also be hubs to engage with surrounding communities and act as event spaces — ideas already explored around the world. In such a view, the old roles of marketing and holding stock get absorbed online, with more focus than ever on warehousing and fulfilment, while physical stores downsize and retain select locations as flagships and experiential spaces. The same can also be said of department stores and malls, many attempting to reinvigorate their floorspace with activity hubs and pop-up stores.

Shopping, an experience

Glancing back to the moments in the film, it's hard to imagine that the mesmerising experience of browsing through certain stores could hold much future in the days to come. It's a sensation all but lost to time, vestiges of retail-gone-by that require an ambience with the potential to surprise. In the media-saturated days we live through, when everything seems to have been already seen and discarded, it's only the rare luxury brand and curious old stores withholding information offline that hold out such promise. Their carefully cultivated or happenstance ambience are also partial to the realm of material reality. With endless devices presenting their adjusted views, no online store could hope to make a comparable impact.

So it may be that shopping as an experience has lost its enchantment while being more convenient than ever. But there are always new, tangential experiences on offer, from participating in virtual runway shows to engaging with people behind the scenes. We can only look forward.

Curious to read more about the the transformation of sales in the new decade? Download The Digital Sales Transformation Handbook and learn how to embrace the transformation for your business and customers.

The Data Handbook

How to use data to improve your customer journey and get better business outcomes in digital sales. Interviews, use cases, and deep-dives.

Get the book